“Serpentes parvulæ fallunt nec publice conquiruntur; ubi aliqua solitam mensuram transit et in monstrum excrevit, ubi fontes sputu inficit et, si adflavit, deurit obteritque, quacumque incessit, ballistis petitur. Possunt verba dare et evadere pusilla mala, ingentibus obviam itur.”

This century entwined cacao consumption with the Mayo Chinchipe-Marañón culture of 5,300 years ago.

Genomic studies hail their Upper Ecuadorian Amazon region as cacao’s origin, connecting ancient strains to the rare Nacional variety, a ‘Fine Flavour cacao’ revered for its distinctive sensory qualities.

Cacao’s millennial journey spanned the Amazon Valley, crossed the Andes, and reached the Pacific coast, spreading to Mesoamerica. The Olmecs crafted and consumed cacao beverages, a tradition that endured with the Maya and Aztecs, who wove cacao into daily life as a revitalizing drink, a sacred elixir, and even currency. Its deep theological roots are reflected in the tree's scientific name, ‘Theobroma cacao’ (Linnæus, 1740), which, in the Mexica empire’s Náhuatl, was called ‘cacahuacuáhuitl,’ its fruit ‘cacahuacintli’ (‘cacao ear’), and its seeds just ‘cacao’ or ‘cacaoatl.’ The word 'chocolate' likely derives from this term, with 'ātl' meaning water, or from a blend of this and 'xococ' ('cosa agra,' sour). Countless trees were sacrificed to paper for this etymology. It traversed the seas in assorted iterations to name cacao-based beverages: 'Cocoatl' (1550s), 'Chachanatl' (1556), and 'Chocolatl' (1570s) and the Spaniards swiftly tamed the flow with their 'e.’

First recorded as ‘coyn’ in Middle English (1150–1500), from Old French ‘coigne’ (‘wedge, die for stamping’) and Latin ‘cuneus’ (‘wedge’). It replaced Middle English ‘mynt’ (from Old English ‘mynet’), from Latin ‘monēta.’

A standardized metal piece issued by a governing authority, marked to indicate its value. Beyond its economic function, it asserts control, upholds social hierarchies, and projects power and cultural identity. Staters (’weight’), one of the earliest known coins, were struck by the Ancient Greeks around the 7th century BCE in what is now western Turkey. Made of electrum, a natural alloy of gold and silver, these pieces had nugget-like shapes with designs (‘types’) on the obverse and incuse punches on the reverse. “…but coinage (νόμισμα, nomisma) has come to serve, by convention, as a substitute for needs. For this reason, it is called nomisma — because it exists not by nature, but by law (νόμῳ, nomos), and it is within our power to alter it and render it useless.”

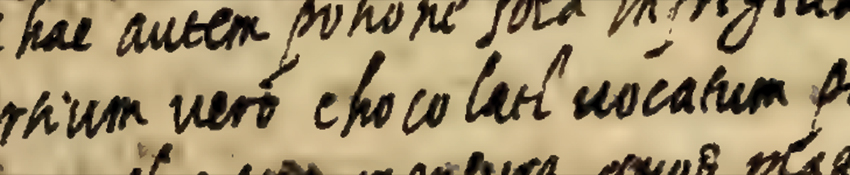

“At in Cacaua Quahuitl, magna deteguntur humanæ fortis volumina. In verteri siquidem Orbe, perq. prisca illa tempora, quæ vitæ hominum erant hecessaria, atque adeo apud alios cumdeessent quærenda, non rependebantur ære. Nondum aureus argenteusuè nummus circumferebatur, aut pecudum, Regumue, aut Principum simulacra metallis cernebantur insculpta. rerum viuebatur permutatione, vt olim factum cecinit Homerus, & fructuum quos recondebant facta alijs copia, mutuum ferebatur auxilium. tandem æra percussa, atque signata sunt, & mille rerum effigies numismatis impressæ conspiciebantur. at in nouum hunc mundum nunquam auritiæ signa penetrauerant, aut caput erexerat ambitio, donec nostri, velis ventouè deuecti, impetum fecere. non vsque adeo splendebant illis argentum atque aurum quibus præcipuè abundabant; auium pulcherrimarum plumæ, lintea quædam gossippina, & gemmæ, quæ ea fert affatim sua sponte tellus, erat diutiarum, & copiarum summa. nondum Armillæ, torques, aut bracialia, nisi fortassis concinnata è floribus, plebi innotuerant, aut Margaritæ erant illis in pretio. nudi penè incedebant, vitam degebant hilarem. neque vastos congerendi thesauros, aut rei familiaris augendæ, veluti de futuro parum sollicitos, cura euigilabat. in diem viuebatur, indulgebatur genio, humili sorte, sed tranquilla & felici, & potissimis naturæ bonis magna cum iucunditate potibantur. Semen Cacauatl erat illis pro nummo, & eo præcipua vitæ præmio, cum opus erat, comparabantur. duratq. in hodiernum vsque diem non paucis in locis hic mos. Quid ni? Quando quibusdam orientalium gentium Cochleæ Veneriæ, & alijs folia quarumdam arborum, & alijs alia pecuniæ gerunt vices. quin & ex eodem semine, quo commercia inibantur, feruebant emporia, & in varios dominos illius ope mercimonia transferebantur. concinnabantq. potum, nodum vini consiciendi ratione reperta, cum tamen nonnulla Vitium syluestrium, ac genera labruscarum apud illos suanpre natura in syluis passim prouenirent, arboresque, & frutices, quibus aduoluenbantur, vuis, acinisq. variorum colorum, & pampinis condecorarent, atque gratuitate sua, incuruarent.”

Hernandez, F. (ca. 1570–1577). De cacaua quahuit seu arbore cacai. In: De materia medica Novae Hispaniae Philippi Secundi Hispaniarum ac Indiarum regis invictissimi iussu. Manuscript, transcribed by Recchi, L. A. [El Escorial, Madrid? : s.n., 1582?], ff.64l–66l. Originally in Latin.

“Verily, in the cacao tree, great things disclose the volumes of human strength. Indeed, in the ancient world, and in those early times, when the necessities of human life were essential, and even when goods had to be sought from others in their absence, they were not exchanged for money. Neither gold nor silver coins were yet in circulation, nor were the images of cattle, kings, or princes stamped in metal. People lived by barter, as Homer once sang of the past, and with the abundance of fruits they stored for others, mutual aid was carried out. Finally, metals were struck and stamped, and thousands of images of things were seen impressed on coins. However, into this new world, never had the signs of avarice penetrated, nor had ambition raised its head, until our people, carried by wind and sail, made their assault. Did not glitter so much for them the silver and gold, which particularly abounded; feathers of the most beautiful birds, certain cotton cloths, and gems, which the earth freely produces in abundance, were the sum of their wealth and riches. Not yet armlets, necklaces, or bracelets, unless perhaps those made from flowers, had become known to the common people, nor were pearls of value to them. They mostly marched naked, living a cheerful life. Neither did they amass vast treasures nor increase family wealth, being little concerned about the future, nor did worry ever arise. They lived by the day, indulging in their inclinations with humble fortune, but tranquil and happy, and enjoying the greatest natural goods with great delight. Cacao seeds (Cacauatl) were for them as money, and they were the main reward of life. When needed, they were exchanged and this custom persists to this day in many places. Why Not? When to some Eastern peoples Venus' shells, and others leaves of certain trees, and to others other things take the place of money. Moreover,from this cacao seed, by which commerce was begun, they conducted trading and goods were transferred to various masters with its aid, and they prepared a beverage with a method discovered similar to the making of wine, although certain wild vines and types of grapes naturally grew in abundance in their forests, along with trees and shrubs – to which they clung – laden with fruits of various colours and decorated with leaves, bending gracefully with their own bounty.”

Hernandez, F. (ca. 1570–1577). De cacaua quahuit seu arbore cacai. In: De materia medica Novae Hispaniae Philippi Secundi Hispaniarum ac Indiarum regis invictissimi iussu. Manuscript, transcribed by Recchi, L. A. [El Escorial, Madrid? : s.n., 1582?], ff.64l–66l. Originally in Latin, translated by antipodes café, 2024.

- UNDER CONSTRUCTION

- Pre-columbian era

- 1492–1510s

- 1520.

- 1520s

- 1505–1553

- 1528–1545

- 1530–1540 >

- 1540-1580

- 1537-1570

- 1550-1592

- 1600

- 1625

- 1650

- 1675

- 1683

- 1700

- 1725

- 1750

- 1763

- 1775

- 1784

- 1800

- 1825

- 1850

- 1875

- 1888

- 1900

- 1925

- 1950

- 1975

- 1986

- 2000

- 2025

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

HEART AND BLOOD

—

In ancient Mesoamerica, cacao seeds were entwined with the divine. The Postclassic Maya honoured Ek Chuah, their merchant and cacao deity, with an April festival. This edible currency was evoked through the metaphor ‘yollotli, eztli’ (heart, blood). While their exploitation was reserved for the elite, by the Late Classic period, cacao could be consumed across all walks of life. However, ordinary people didn’t get poorer wittingly by swallowing their coins, furthermore it was drunk in concord—otherwise, heart and blood.

A MAN NAMED JUAN (i)

—

Named for his skin, Juan Prieto (or Moreno) was among the first chronicled African descendants to reach the New World. Though not a chattel slave, he served Columbus and bore the Admiral’s ire—as revealed in a 1500 inquiry into cruelty during Hispaniola’s governance. In 1501, Ferdinand and Isabella authorized the new island’s governor to import Christianized African slaves, known as ladinos, marking a pivotal step in institutionalizing the transatlantic slave trade. The following year, the monarchs backed Columbus’s fourth voyage but urged him to bypass Hispaniola and forswear taking slaves. According to lost writings attributed to Columbus’s son, published posthumously and this exploratory mission led to the first European encounter with cacao when, near Guanaja Island, they seized a canoe: “[carrying] many of those almonds, which the people of New Spain use as currency; these seemed to be highly esteemed by them, for when their load was placed on the ship, I noticed that if any of these almonds fell, everyone immediately bent down to pick it up, as if they had lost an eye.” It seems unlikely that Columbus and his crew would have entirely overlooked cacao’s significance if even his youthful son recognized its value. What is well recorded is that after Columbus’s death, Moreno participated in Central America’s colonization, now named for his steps as Juan Portugués.

A SOLDIER OF FORTUNE

—

Tenochtitlan ended June 1520 with a sorrowful night for the Spanish conquerors. Bernal Díaz recorded his lack of greed for gold and focus on survival, justifying a swift collection of only four known precious stones from a small pot. Without Hernán Cortés noticing (as he soon thereafter secured the entire hoard), The soldier of fortune escaped with nothing less concealed in his chest than the cost of living for 240 years in the New World, or 60 xiquipillis of cacao (roughly eight modern sacks), or 120 prime slaves—those who knew how to dance.

‘FELICI MONETA’

—

Slavery in the Mesoamerica differed. It was not inherently tied to race. Freedom was often temporarily alienated through contracts, usually to settle debts. For instance, individuals could sell themselves or their children, but slavery wasn’t hereditary—as with the Aztec Empire’s key founder. Slaves could have families and property, including slaves. Enslaved people were mostly women, as were the workers of the oldest profession. Prostitutes often turned to slavery when aging or becoming less attractive. In Nicaragua, a session with a prostitute could cost 8 to 10 cacao seeds. The idea of money growing on trees attracted the conquerors. In October 1520, Cortés described cacao as “a fruit like almonds, that they sell ground; and they have it in such quantities that it is treated as currency throughout their lands, and with it are bought all necessary things in markets and elsewhere.” Yearly, Tenochtitlan reaped about 25 million cacao seeds in tributes, with about one third from the Soconusco area alone, renowned as the center of high-quality cacao production. In 1521, Zuazo noted, “There is a coin among them with which they buy and sell, called cacahuate; it is the fruit of certain highly prized trees, from which they make another concoction for great lords, which they say is a very delicate thing.” Driven by a thirst for wealth, known and anonymous conquerors quickly turned their focus to cacao, not for its culinary use, looting Moctezuma's vast reserves and later controlling and expanding its production—essentially for minting what D’Anghiera described in 1524 as the ‘felici moneta.’

A MAN NAMED JUAN (ii)

—

From scratch, the Atlantic trade proved profitable for merchants and, moreover, for the Iberian Crowns, who taxed the sales and enriched with African slaves performing any task in the conquest of the Americas—even as cannon fodder, lured by freedom and land. In some expeditions, they outnumbered the Spaniards, but for the conquest of Mexico, few partook due to their high cost. A 50-peso slave in Europe doubled in price across the ocean, reaching 16 xiquipillis of cacao (ca. 2 modern sacks). Only the privileged could count that amount of seeds—such as Cortés’s cousin and secretary, Alonso Valiente, who bought and baptised a young Wolof, renaming him Juan Valiente. Residing in Puebla since its foundation, and after years of servitude, in 1533, both agreed on manumission for the shares of four years of conquest expeditions.

Pizarro’s campaign was regularly supplied with African slaves, including two for his personal use: a master of artillery and Juan, who became a military commander. Pursuing his goal, Juan left Peru with Almagro and later joined Valdivia. Having a horse, he commanded the slaves; as a slave, he commanded the horses. Juan survived the Andes and the early stages of the brutal conquest of Chile. In Santiago, his freedom saw its foundation: he was granted an estate, learned about nursing, and married Juana, a former African slave of Valdivia, who, years later, gave Juan a large encomienda—an exploitative system through which the Spanish Crown granted settlers the right to extract labour and tribute from Indigenous peoples, often working them to death. Running a distinguished repartimiento de indios near Concepción, Juan continued living and fighting as a free man, but his payment never reached Antonio. In December, there's no brave one who doesn't tremble, but he never knew he died as a slave, and nobody knows the names of those under his encomienda, nor if any joined the Battle of Tucapel and still fight for Wallmapu, nor if any ever convinced Juan to become that sort of Valiente.

TONGUES

—

Doubtless it befell during Cortés’s calculated return to Spain in 1528 to dazzle Emperor and court to ‘dress myself in the cloth I spun and wove’ in the New World. Moreover, he conveyed indigenous nobles and sons of Moctezuma, alongside unseen fauna, delicate mantas, and artifices. Some even claim it outright, inviting others to say it mayhap came earlier with unrecorded correspondence, or by Franciscan monks, or with Cistercians at Nuévalos in 1534; or three years later when the Viceroy of New Spain described counterfeit cacao seeds to the King, or as recorded when Black Friars led K'ekchi’ chieftains to meet Prince Felipe in 1545. Speaking of K'ekchi', their lament echoes:

‘Ay tiox c'ajo' tacui' rahil ra'bilquil li’ ‘Oh God! How harsh is what you tell—

na̲caye̲ chanru nacac'oxla ma a'in tz'akl, that I should believe this is not the truth,

li ya̲l li na̲caye̲.’ but another that you tell me.’

The disembarkation of cacao and its beverages to Spain remains undiscovered… yet tongues were already conquered."

‘SHARK FEEDING’

—

The insanely destructive force of the Iberian invasion forged the very essence of conquest. Yet forced depopulation neither vanquished avarice nor converted settlers into labourers. Instead, it stoked the furnace of the transatlantic slave trade, through royal and black markets, forcing repopulation with more resilient and profitable slaves. Alongside the subjugation and displacement of indigenous peoples, the 16th century saw the Crown granting nearly 120,000 import licenses. In just 50 years of conquest, Hispaniola changed its estimated 400,000 native inhabitants to 30,000 black slaves, 1,100 whites and just 200 indigenous people. A trend echoed in the ‘Elegías de Varones Ilustres de Indias’:

“… Faltaua ya de indios el avio

Por el vniuerſal acabamiento,

De ſuerte que hay en eſtas heredades

Negros en exceſsiuas cantidades.

Tienen la tierra qual ſe deſſea

En temple y abundancia coſa rica,

En grande aumento va cada ralea,

Y con grande vigor ſe multiplica,

Tanto, que ya parecen ſer Guinea,

Hayti, Cuba, Sant Ioan y Iamayca; …”

Despite genocide, cacao consumption grew amid upheavals in customs that lifted taboos restricting its use by lower indigenous classes. It also persisted as currency for various transactions, including tributes—now paid to Europeans, even in regions without cacao production. Total control over cacao became a priority, driving trade regulations and the expansion of production in both existing and new plantations (such as Colima, 1528) and territories (like Trinidad, 1525), gradually spreading throughout the region. In 1527, selling cacao by seed and without an official seal was prohibited, a ban reinstated in 1536, when a load of cacao sold for 6.6 pesos in Ciudad de México, and a black slave for 100 pesos. Iron branding of indigenous people for slave trade after displacement was practiced, as was the counterfeiting of cacao seeds by natives, reported to the king in 1537. That year in Nueva Cádiz, indigenous and black slaves were banned from walking in town after dusk, drinking wine, carrying weapons, or fleeing—punishable by amputation of an ear and leg after 40 days. Meanwhile, settlers were finally prohibited from feeding their slaves to sharks.

PESOS PESADOS

As the yoke grew burdensome, another weight did wax heavy: prices.

From the mid-1540s to 1551, the value of cacao trebled, drawing 100 seeds per Real. Izalcos’ twin cacao encomiendas swelled wealthiest, yielding 8 million seeds in tribute—a sum soon quadrupled–eclipsing the fading Soconusco. Yet the richest settler was not an encomendero, but a grim Toledean, mocked posthumously for his humble disguise, as though his fortune had sprung from the dust, vending cacao by seeds ‘pon a market blanket. The son of hidalgos, Alonso de Villaseca crossed the Atlantic and wed to the affluent Francisca Morón acquiring vast haciendas replenished with cattle. His income of 150,000 ducados —so 'twas claimed— was drawn not only from these, but from mines, lands houses, and an ever-growing treasury of lucrative holdings, numbering hundreds of slaves, servants, and dependents. So vast their number, he oft inquired of names and masters, learning at times, it was himself. For the Crown he kept his head, and when creole tumult arose upon his vast demesnes, he dispatched two hundred armed horsemen and 100,000 pesos, with no demands. Corruption and fraud, though not absent, swelled his fortune to one and a half million pesos, as history doth tell. “Even the very stones side with Villaseca” reported the Virrey to the King, as his banishment and fines for his mistreatment and excessive tributes to the natives were rescinded. Lo, sight-bearers kneel with watchful orbs, before him who, with pious mien, doth dispense alms. Not Franciscans, Dominicans, nor Agustinians swam in his silver cauldron, but Jesuits. Power seeks power, and with ‘La Compañía de Jesús’ he sought the highest seat. Though he gave not when entreated, yet did nigh a quarter million pesos pass unto them from his hand, and succour of all kinds from his fist, as when thousands of unpaid Tacuba natives toiled to rear a temple in but three moons. Today, countless faithful beseech an end to the growing scourge of organized crime in mining and for all sorts of miracles beneath the Spanish Image of Christ, ‘El Señor de Villaseca,’ known for its darkened hue as ‘El Cristo Negro.’

AT SIMMER

After years of missionary outcry against systemic abuses of indigenous peoples, Pope Paul III defied prior Doctrine of Discovery decrees—Dum Diversas (1452), Romanus Pontifex (1455), Inter Cætera (1493)—issuing in 1537 the brief Pastorale Officium and the bull Sublimis Deus. In the latter he declared ‘[natives aren't] ‘brute animals suited for servitude' (…)‘and that they may and should remain freely and legitimately in possession of their liberty and dominion of their property, nor are they to be reduced to slavery.’

Betwixt humanitarian appeals and demographic destruction, the Spanish Crown issued the 1542 New Laws—formally abolishing indigenous enslavement while declaring natives royal vassals. Though the immediate abolition of encomiendas became imperative, settler resistance preserved the genocidal system for generations, alongside new exploitative schemes like the repartimiento and mita.

The latter, introduced in 1570 by Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, transformed the Inca Mit'a practice of mandatory state service into coerced labour, primarily for Potosí’s mines, where communities surrendered one-seventh of their men to deadly conditions. Subdued simmered shifts, yet native women kept preparing cacao: in markets now with Spanish customers, in homes now with Spanish husbands and masters, in taxpaying affairs now for Spanish lords and still in receptions—now of missionaries.

INGESTION

Meanwhile, in the ‘Insubordinate Land’ [as the Zapatistas renamed Europe in 2021], cacao’s conquest advanced slowly, meeting entrenched disdain for acknowledging the ongoing somatization of cultural values from the Americas. ‘More swine’s drink than human fare,’ scoffed even the outspoken critic of Spanish practices, Girolamo Benzoni, in a treatise dedicated to Pope Pius IV. Puritanical Catholics also faced chocolate with the ecclesiastic fast. Jesuits — who traded cacao — were wilfully supportive of its consumption, as were all potentates in favour of the nourishing wine already accepted. It took centuries to dilute the discussion in favour. Scholastic deductions also weighed in, along with fears of addiction. Around 1575, the royal physician Francisco Hernández noted: ‘The drink we call chocolate, well-known and widely consumed from England to Germany and even Constantinople, is composed in a way that pleases; and it is true that it fattens noticeably, and if used frequently, it can lead to thinning and other harms.’ The Atlantic widened daily. In 1591, the creole Doctor Cárdenas observed: ‘Regarding the harms and benefits it produces, I hear everyone give their opinion. Some abhor chocolate, making it the inventor of all diseases that exist. Others say there is nothing like it in the world, (…) Thus, there is no one who can make sense of the public opinion on this matter. Only the divine Hippocrates can bring us out of this confusion with that cryptic sentence he said: not everything for everything, but each thing for what it is.’ In his Tratado breve de medicina y de todas las enfermedades, published in Mexico the following year, Friar Agustín Farfán prescribed morning hot chocolate for the constipated.

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

Demo Content

| COMMENTS | DETAIL |

|---|---|

| i. Moneda de Cambio | 4000 cacao seeds (glued to the wall) |

| ii. Moneda de Cambio | 2 cacao sacks (mound OR hanged) |

| iii. 2 Marcos Alemanes | Diptych: 2 frames, each with 2 chocolate coins (both sides)—1 Deutsche Mark and 0.50 German Euro. |

| iv. Hobby of Kings | Chocolate coin collection (+500 pieces) |

| v. Dĕūro | Chocolate coins minted in Madrid |

| vi. Cambio | Exchange booth (1 Euro ≙ 1 Dĕūro) |

| vii. Cambio | Exchange machine (1 Euro ≙ 1 Dĕūro) |

| DISPLAY | … |

| Logroño City Hall | i,ii,iv,v,vi (2022.11) |

| Obrador, Montevideo | i,ii,iii,v (2023.01) |

Download: Illegal Tender (comments -PDF)

(PAGE UNDER CONSTRUCTION)

antipodes café

_